In the fast-paced world of software development, new tools, languages, and frameworks appear with dizzying speed. Yesterday’s cutting-edge innovation is today’s legacy debt. For Chief Technology Officers (CTOs), architects, and engineering teams, the challenge isn’t just finding new technology radar—it is deciding what to embrace, what to test, and what to ignore.

Enter the Technology Radar.

Originally popularized by the global software consultancy ThoughtWorks, the Technology Radar has become an essential strategic tool for modern organizations. But what exactly is it, and how does it turn the chaos of the tech landscape into a coherent map?

The Definition

A Technology Radar is a visual document that tracks current and future technologies within an organization. It serves as a portfolio management tool, helping teams objectively assess the risks and rewards of the tools they use.

Think of it like a traditional radar screen on a ship. It shows you what is close (technologies you are currently using), what is on the horizon (technologies you should be researching), and what you should avoid steering into.

The Anatomy of the Radar

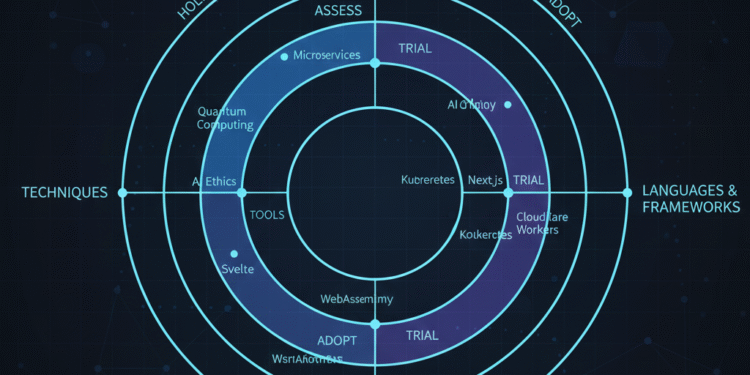

While companies can customize the layout, the standard Technology Radar consists of a circle divided into Quadrants and Rings.

1. The Quadrants (Categories)

The circle is sliced into four sections, each representing a different type of technology:

-

Techniques: These are elements of a software development process, such as “Micro-frontends,” “Chaos Engineering,” or “Domain-Driven Design.”

-

Tools: Software components used by developers, such as databases, version control systems, or CI/CD pipelines (e.g., Jenkins, Docker, Jira).

-

Platforms: Things that we build software on top of, such as mobile operating systems (Android/iOS), cloud providers (AWS/Azure), or virtual reality systems.

-

Languages & Frameworks: The code itself and the scaffolding used to write it (e.g., Python, React, Rust, .NET).

2. The Rings (The Lifecycle)

The blips (technologies) are placed on the radar within concentric rings. The closer to the center, the more “approved” the technology is.

-

Adopt (The Center): These are technologies that the organization feels strongly about. They are proven, mature, and low-risk. The advice here is: “We should be using this for all new projects.”

-

Trial (The Second Ring): These are technologies that have been successful in a pilot project. They show promise, but the organization wants to see them used in a slightly riskier environment before fully committing. The advice is: “Worth pursuing on a project that can handle the risk.”

-

Assess (The Third Ring): These are technologies that look interesting but haven’t been tested yet. The goal here is to understand how they work and if they solve a problem. The advice is: “Research this, read whitepapers, and build a prototype.”

-

Hold (The Outer Ring): This is the “Stop” sign. A technology in this ring might be too new and unstable, or it might be an old legacy tool that the company wants to phase out. The advice is: “Proceed with caution or do not use.”

Why Do You Need One?

If your company has five developers, you probably don’t need a radar; you can just talk to each other. But as organizations scale to 50, 500, or 5,000 engineers, the radar becomes vital for several reasons:

1. Preventing “Resume-Driven Development”

Without guidance, developers often pick the newest, shiniest tool just to learn it for their resume, even if it’s not the right fit for the company. A radar provides governance, ensuring that technology choices align with business goals.

2. Standardization vs. Innovation

A radar strikes a balance. It standardizes the “Adopt” ring (so everyone uses the same cloud provider, simplifying hiring and maintenance) while encouraging experimentation in the “Assess” ring (so the company doesn’t fall behind).

3. Knowledge Sharing

If Team A in London spends six months testing a new database and finds it terrible, they can put it in the “Hold” ring. Now, Team B in New York won’t waste six months making the same mistake. The radar acts as a collective memory.

4. Managing Legacy Debt

By explicitly moving an old framework like AngularJS or an outdated version of Java into the “Hold” ring, leadership sends a clear signal: “We are phasing this out. Do not start new projects with it.”

How to Build Your Own

Creating a Technology Radar is not a one-person job. It should be a democratic process involving senior engineers, architects, and product leads.

-

Gather the Data: Survey your teams. What are they using? What do they hate? What are they excited about?

-

The Review Session: Hold a meeting to debate the placement of blips. This is where the magic happens. A developer might argue that “GoLang” should move from Trial to Adopt, while a security engineer might argue it should stay in Trial until security scanning tools improve.

-

Publish: Make the radar visible. It can be a PDF, a page on the company intranet, or an interactive website.

-

Iterate: A radar is a snapshot in time. It must be updated quarterly or bi-annually. Technology rots quickly; a radar from 2023 is likely useless in 2026.

Conclusion

A Technology Radar is more than just a colorful chart. It is a communication device. It bridges the gap between the chaotic reality of software development and the strategic needs of the business. By visualizing the technological landscape, companies can make deliberate, informed decisions, ensuring they are not just drifting with the current, but steering toward the future.